T R A V E L S

INTO THE WILD

Australia’s Shark Bay makes for a full-on Nature Immersion

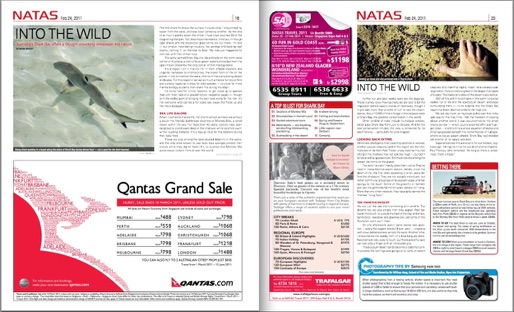

The first shark fin broke the surface minutes after I’d launched my kayak from the sand, and was soon joined by another. By the end of an hour’s paddle down the shore I must have counted 35 of the disquieting triangles.

Not Jaws-style maneaters, mind you - though tiger sharks and the occasional great white are out there, I’m told - but smaller, more benign cousins, like sandbar and black-tip reef sharks, coming in on the tide to feed. My ride just happened to coincide with their dinner hour.

The aptly-named Shark Bay sits like a dimple on the northwest corner of Australia, a cleft of blue-green waters protected from the open Indian Ocean by the long barrier of Dirk Hartog island.

It’s a region rich in marine life – from affable dolphins and ungainly manatees to stromatolites, the oldest form of life on the planet – not to mention the eerie charms of the surrounding desert landscape. For this reason it serves as much a mecca for nature fans and outdoor types as it does for wild species. (I counted far more marine biology students than shark fins during my stay.)

I’d come here myself for similar reasons, to get close-up to species that until then had only graced nature magazine pages – though with the added quirk of bringing my own boat along for the ride. It’s not everyone who carries a full-sized sea kayak that folds up and fits into a backpack.

Sea Life Galore

When it comes to marine life, the charm-school winners are without a doubt the friendly bottlenose dolphins of Monkey Mia, a small resort within the bay. For more than 40 years, visitors have been delighted to stand waist-deep in the shallows while dolphins swim within nuzzling distance. It’s a regular ritual for the dolphins during their daily feed.

These are also among the best-studied dolphins in the world, and the only ones known to use tools (sea sponges protect their snouts while they dig for food.) It’s no surprise that Monkey Mia alone draws visitors from all over the world.

Further out and less readily seen are the dugongs. Those clumsy, slow-moving creatures are said to be the inspiration behind sailor’s stories of mermaids, though it might take more than a bottle of rum to see the resemblance. About 10,000 of them forage in the eelgrass beds of Shark Bay, the greatest concentration in the world.

Not every inhabitant is so benign. Tiger sharks are abundant in the area, as are venomous sea snakes and stonefish, which sit concealed on the bottom like deadly rocks. However it’s rare to hear of injuries or attacks. A little caution goes a long way.

Other wildlife of note include humpback whales, which pass Shark Bay from July to October. And for the less conservation-minded, the area is renowned for its sport fishing – particularly for pink snapper.

One of the many friendly bottlenose dolphins at Monkey Mia.

Looking Back in Time

While less photogenic than cavorting dolphins or whales, another popular drawing card of the region are the stromatolites of Hamelin Pool. These lumpy, rock-like mounds sitting in the shallows may not look like much – but don’t be deceived by appearances. Stromatolites are among the oddest life forms on the planet.

The word ‘ancient’ hardly does them justice. They’ve lived in these bathtub-warm waters literally since the dawn of life, the first ones appearing 3 billion years before the dinosaurs. They are not actually individuals, but rather communal groupings of blue-green algae and feel spongy to the touch. Some of the growths in Hamelin pool are thought to be 50 million years old and still living. More than any other creature, they have aptly earned the moniker ‘living fossil’.

Er... which way to Hamelin Pool?

The Painted Desert

It’s not just the sea that’s brimming with wildlife. The deserts too are less empty than they appear. Peer between the brush, or outside the heat of the day, and emus, bandicoots, wallabies and goannas are just some of the Australian icons you’ll meet.

On one afternoon’s walk I came across two goannas – easily the biggest lizards I’d ever seen - stepping with slow deliberateness across the sand. Another time, I encountered the stubby form of a blue-tongued skink. Fascinating to see, scaly to touch, but those powerful jaws can lock onto a finger with an intractable grip.

A goanna searches for supper in the desert scrub (left). Those inimitable Aussie roadsigns (right.)

Those auburn desert sands become a slate that communicates the comings-and-goings of all sorts of desert creatures: bird, mammal, reptile, insect. Here a snake’s sidelong motion, there a crow’s twig feet, or the deeper moon pads of a rabbit. The tracks tell a story of the desert’s abundance.

With all this within its compass - the warm turquoise waters full of life and the spectacular desert landscape surrounding them - it’s no surprise that the Shark Bay region has been deemed a World Heritage site.

Out of the Wild

My last day there, as my kayak glided over that milky jade sea for the final time, I felt the freedom of soaring above another world. I was accustomed to the small sharks by now – which usually splashed off in alarm as I got close – and this time a whole squadron of skates and sting-rays passed beneath me, some the size of hubcaps, others as big as wagon wheels. Shark Bay had revealed yet another of its natural wonders.

Experiences like this are tonic for our frenetic, digitized age. They bring to mind the words of another traveller, Paul Theroux, who remarked: "As long as there is wilderness, there is hope."

SHARK BAY’S TOP TEN

1. Dolphins of Monkey Mia

2. Stromatolites in Hamelin pool

3. Guided adventure tours

4. Watersports – sea kayaking, windsurfing, kiteboarding, snorkelling

5. Bushwalking in the desert

6. 4-wheel driving

7. Fishing and boat charters

8. Spring wildflowers (August, September)

9. Little Lagoon near Denham

10. Camping

TRAVEL NOTES

GETTING THERE:

The most common way to Shark Bay is to drive there. Denham is 820 km north of Perth, or a 10 hour car trip. Some of the region’s attractions cannot be reached by regular 2WD vehicles, however, Public transport options are the Greyhound bus, operating daily from Perth ($140) or regional airline Skippers, which flies to the Monkey Mia from Perth several times a week ($390).

WHEN TO GO: The best times to visit are June to October, the winter and spring. The views of spring wildflowers on the drive up are world renowned. With temperatures in the mid-20s and light winds, the climate is at its gentlest. Summer months can be exceedingly hot.

WHERE TO STAY: Most accommodation is found in Denham, the one village in the region. These range from campgrounds ($18 a night) to small beach cottages ($50) to plush seaside chalets and Heritage Resort Shark Bay ($160)

This article article was first published in TODAY and can be found online here.

by Mark Malby

Wednesday, 24 August 2011

A black-tipped reef shark forages for dinner in the tidal shallows - photographs Mark Malby